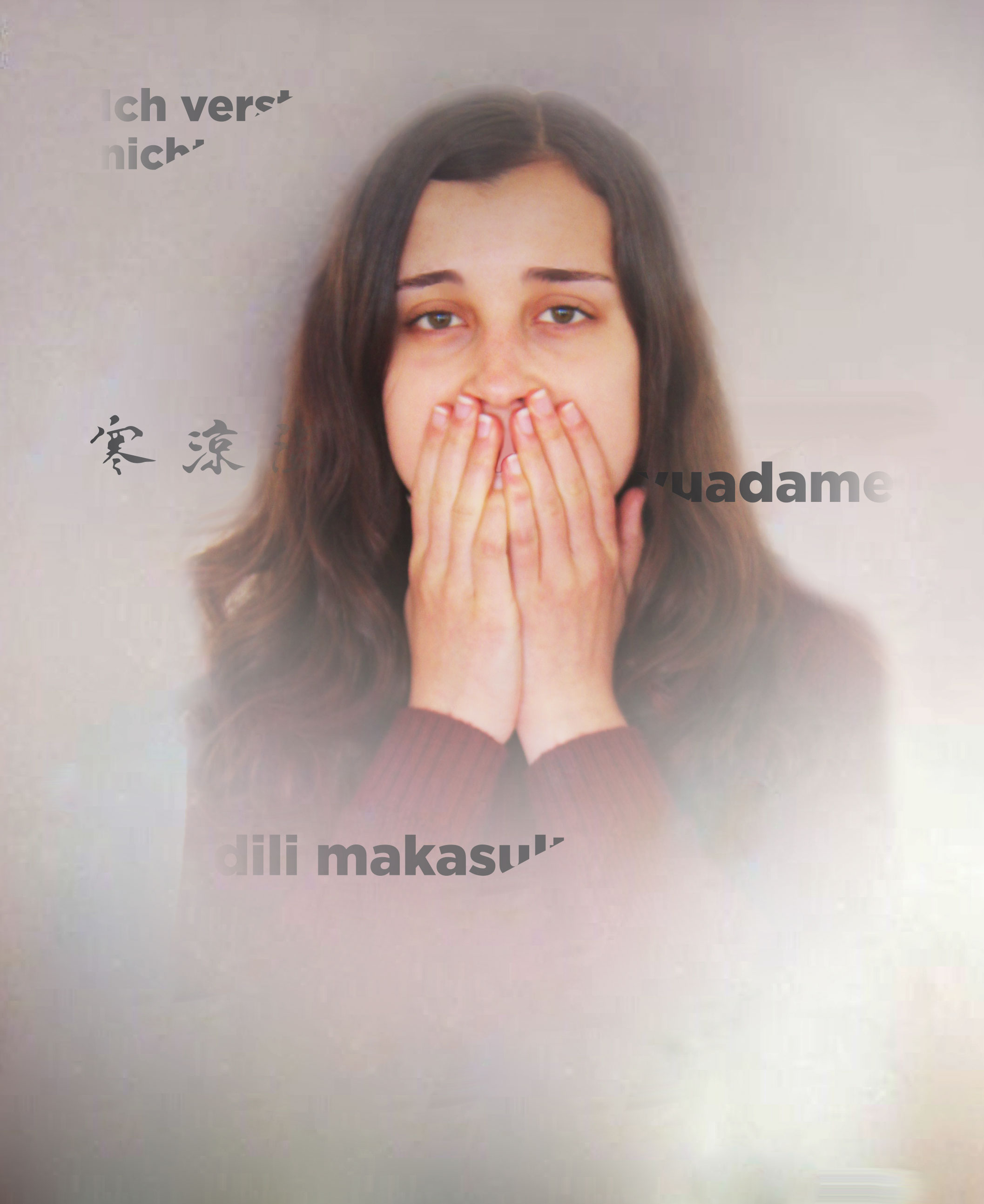

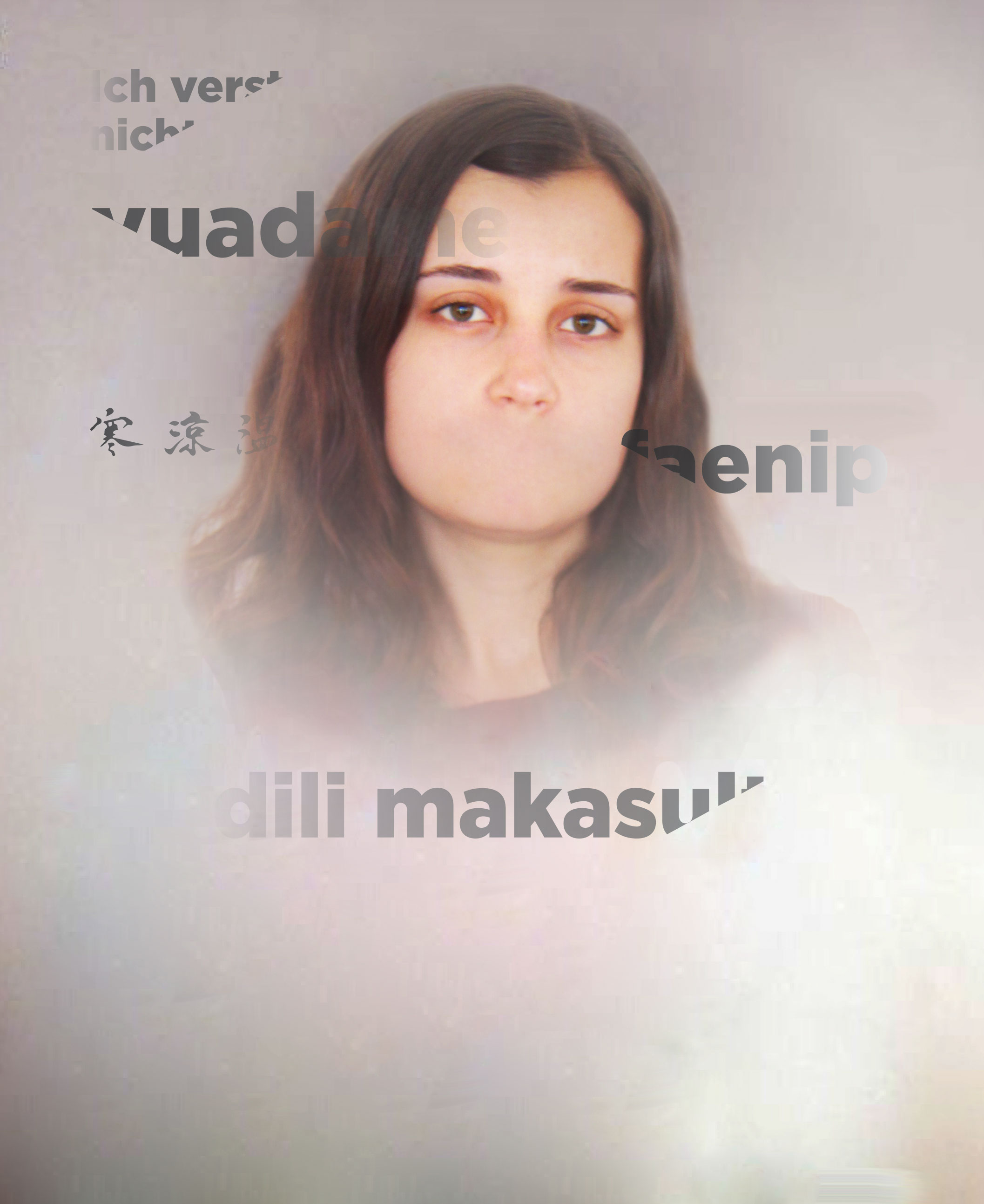

Lost Language

By Amanda Perkin

When we develop as humans it is second nature to grow, walk, talk and learn. However, as we evolve, somehow we also let go of our native languages.

Given today’s diverse range of cultures, you would believe that it is first nature for a person to retain their traditional language, which is so tightly bound to the concept of their personal identity [30]. Yet this is the problem in itself. Whether you have been born in a westernised country and/or you have relocated further away from your place of birth, it is easier to lose a language than you would think. For example, exiles who have been imprisoned due to war, face the difficulty of retaining their language. Unfortunately, the loss is one of the single most important connections for them to their homeland [30]. Exiles introduced to a new and hostile environment have their first language adversely affected by trauma. This change is a forced degradation on language due to the need to adapt and survive.

However, not just the serious displacement of war is to blame. Language can be lost simply because of being born in a country where your parents or ancestors are not from originally. In fact, language decay can easily start to occur as a person is learning and adapting to a different language [30]. According to Michael Rodgers (2014), after having moved to the UK at the age of twenty-three he began to lose touch with his first language. He says: “people always look at me sceptically when I say I have ‘lost’ my Dutch language… When my mother calls, I need to put her on hold while I go and get the thesaurus.” If Michael experienced this after a number of years then where does this leave me and you? Has language decay started occurring to you too, or maybe it already has?

Ansh Jain, another victim of language decay, had it happen to him after relocating from one country to another. Jain is from Delhi in North India. His native language is Hindi, however seven years ago his family moved to Bangalore in South India and he noticed a very different way of communicating upon arriving there. “On my first school day in Bangalore the first odd thing struck me, which was that everyone here only spoke English in school” [31]. With English as the first and official language of the area, Jain was left with the limited option to adapt to the given language.

Shel Silverstein (2007) reflects on the mystery of language decay by addressing an exchange with nature, often ignored by our generation, in the poem Forgotten Language [32]. Shel’s words are a dedication to our ever-changing society, which can be so fast paced and dynamic, that forgotten languages are becoming more common than ever before. Like we do as humans, Shel describes a connection he shared in the past with nature “Once I spoke the language of the flowers, once I understood each word the caterpillar said...” He imagined a world where he was able to understand and appreciate the things surrounding him, “Once I smiled in secret at the gossip of the starlings, and shared a conversation with the housefly in my bed.” Though he ends the poem on a sad note, after losing the connection that he once shared, “...how did it go? How did it go?”

Many of us simply never bother to learn the legacy of our traditional language or vernacular dialects. The characteristics of language are rarely passed down between generations with great attention and remain fluid and ever-changing.

So what is my experience in this? As a child I had many options to learn my family’s languages. In my blood is a combination of English, Lebanese, German, Hungarian and the possibility of French which was closely linked to the French pirates. However, when you have so many cultures that you’re a part of, do you really become fluent in all of them? I found that as I grew into the person that I am now, I had never really taught myself the many languages that my ancestors and relatives had spoken, simply because there were too many. Sadly, as a result of this, I have little knowledge of my ancestors’ languages and I have only myself to blame.

Give or take, language decay is an inevitable part of life for a number of people. It can happen after a person has relocated to a different country or they have been brought up in a place where their parents were not born. Unfortunately, sometimes there is little that can be done to help cease a language complication which is already sure to happen.

[30] Luu, C. (2016). Language Loss In a time of War. Retrieved from http://daily.jstor.org/language-loss-in-a-time-of-war/

[31] Jain, A. (2011). Losing touch with your native language? Retrieved from https://www.lonelyplanet.com/thorntree/forums/like-a-sore-thumb/topics/losing-touch-with-your-native-language

[32] Silverstein, S. (2007). Forgotten language. Retrieved from http://www.americanpoems.com/poets/Shel-Silverstein/19767

“When my mother calls I need to put her on hold, while I go and get the thesaurus.”

“Sometimes there is little which can be done to help cease a language complication which is already sure to happen.”